GMAT Verbal: Subjunctive

The subjunctive usually refers to things that have not happened yet, whether we really want them to happen (commands, wishes) or not (suppositions, conditional statements, fearing). The subjunctive appears in very specific contexts; we shall cover the most common ones, and some of the less common ones! Please note that the subjunctive on the GMAT is not common. If your Verbal scores are low, direct your studies toward:

- subject-verb agreement

- verb tense, comparisons

- parallelism

The subjunctive exists in many languages, though other languages use it more than we do in English, where it’s a somewhat strange and slowly disappearing form.

What does the subjunctive look like?

The present subjunctive looks exactly the same as both the imperative (used in direct orders, like Go home! or Be careful!) and the part of the infinitive that isn’t the word to (to poke or to prod). Some call this the “plain form” of the verb, since it’s the same in all three settings (stop, drop, roll). It doesn’t get different endings for being in the past tense (like take vs. taken) or in the third person singular (I eat vs. she eats). Since Sentence Correction on the GMAT is completely dominated by third-person verbs (he/she/it jumps, they jump), the subjunctive will stand out more often:

Indicative (“normal”): She puts ketchup on her eggs.

Subjunctive: I suggested that she put ketchup on her eggs.

It definitely stands out! You won’t be able to tell a friend “She put ketchup on her eggs!” without your friend wondering whether you’ve been hit in the head too many times, because the subjunctive doesn’t live on its own, outside of a few set phrases that are basically fossils, remnants of a time when the subjunctive was more common in English (and we’ll cover those too). When you need a present subjunctive, think of how you would form the infinitive (to sing, to cut) and remove the to: that’s your present subjunctive (or “plain form”).

The past subjunctive looks the same as the normal (indicative) form, except in the verb to be.

The future subjunctive as it is traditionally taught looks different from the indicative and other subjunctives in all forms; some say that because it’s so different, we should call it something else and not the future subjunctive at all. As mentioned, this because your understanding of how this works is deeply affected by the way you were taught (for most non-native speakers of English) or the fact that you weren’t taught it at all (for most native speakers). No matter how or whether you were taught the subjunctive, though, these are the forms you could see on the GMAT.

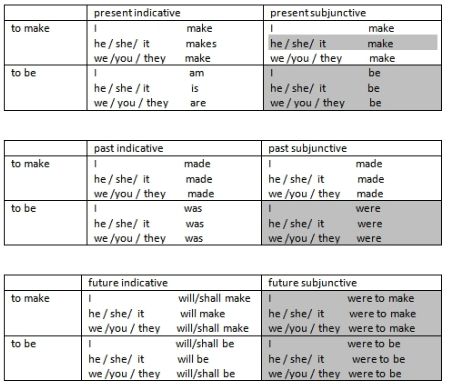

Here is a chart of the subjunctive to refer to:

I’ve highlighted the places where the subjunctive differs from the “normal” indicative. In the future tense, you see that I have “will/shall”; traditionally, “shall” is the simple first-person future form (I/we shall, but he/she/it/you/they will), though you are not likely to see it often in American English. “Shall” can still be used to show certainty or obligation (You shall not pass!), and also appears in legal language.

Where will I see the subjunctive?

There are some common places the subjunctive can appear in English; we will be covering all of these in this series:

- wishes (I wish that I were able to drive a motorcycle or may the best man win)

- suppositions (If I were to go to the party, I wouldn’t finish painting the house)

- demands and commands (She demanded that he leave her house immediately)

- suggestions and proposals (I suggest that she think about it more)

- conditions contrary to fact (If I were master of the universe, college tuition would be free)

- statements of necessity (It’s necessary that they be there for your safety)

- fearing with lest (I filled her car with gas lest she run out on her cross-country trip)

- idiomatic phrases (As it were or be that as it may or . . . need only . . .)

Wishes

Wishes are one of the two most common uses of the subjunctive in spoken English (suppositions the other, which we’ll cover next time), when you use to wish, you use the past subjunctive were, even though the wish is not taking place in the past:

He wishes he were on vacation.

She wishes that the sun were out.

Note that you can use that, or not use it; the wish stays the same.

Suppositions

A “supposition” (which is the noun form of “suppose”) is a sentence theorizing or guessing about possible outcomes of actions that haven’t happened yet, or options being considered. Suppositions are more common in spoken English than in written English, but the subjunctives are slowly being replaced by indicatives (which are normally used in factual conditions). Eventually the indicative forms will be correct formal English but not in time for your GMAT Test Date:

-Supposition (subjunctive): If I were to be elected president, the first thing I would do is replace our complex income tax with a higher, but simpler, sales tax.

-Supposition (indicative, common in spoken English now, not correct on the GMAT): If I am elected president, the first thing I would do is replace our complex income tax with a higher, but simpler, sales tax.

-Compare those to a factual condition: If I am elected president, the first thing I will do is replace our complex income tax with a higher, but simpler, sales tax. It’s not “factual” in the sense that it has happened, but rather is as factual as a promise or a prediction (or a threat!).

Demands and Commands

Demands and commands are among the most common written uses of the subjunctive; they will almost always be seen with the subordinating conjunction “that” (though some can do without), which will signal the beginning of the actual command or demand. Here are some examples of words that can generate a subjunctive command:

- to ask (that)

- to command (that)

- to demand (that)

- to desire (that)

- to insist (that)

- to request (that)

- to urge (that)

- to require (that)

- to decree (that)

. . . but many of the above verbs can also be used in another way, expressing a demand or command without a subjunctive:

- to ask [person] to [action]

- to command [person] to [action]

- to urge [person] to [action]

- to require [person] to [action]

. . . and some “command” verbs will usually or always use the second form shown above:

- to tell [person] to [action]

- to order [person] to [action]

It can be frustrating to have it all come down to idiom/vocabulary, and in your own writing of course you have the option of avoiding the subjunctive in most cases, but you want to know how to handle yourself if you run into a question with a subjunctive in a dark alley of the GMAT.

Suggestions and Proposals

These statements work similarly to demands and commands, covered in the previous article. Certain words can trigger a subjunctive statement, sometimes or always accompanied by the subordinating conjunction that, which signals the beginning of the suggestion or proposal:

- to advise (that)

- to ask (that)

- to desire (that)

- to propose (that)

- to recommend (that)

- to request (that)

- to suggest (that)

- to urge (that)

Some of these verbs also function without a subjunctive:

- to advise [person] to [action]

- to ask [person] to [action]

- to urge [person] to [action]

And as with commands and demands, some verbs of proposal will idiomatically almost always avoid the subjunctive:

- to want [person] to [action]

- to beseech [person] to [action]

- to plead with [person] to [action]

- to implore [person] to [action]

Conditions Contrary to Fact

Similar to the suppositions discussed in an earlier article, conditions that are counterfactual (or hypothetical) use the subjunctive when the consequence is either not likely or known to be completely untrue. These conditional statements come in two forms, present and past, and the form of the subjunctive used will change.

Present contrary to fact conditions

Present contrary to fact conditions use the past subjunctive with a conditional word (would, could, should, might) and a plain form main verb to express the consequence of an event considered false or highly unlikely by the speaker:

- If she pulled a gun on me, I could use my martial arts training to kick it out of her hand!

- If I were rich beyond my wildest dreams, I might consider buying you a cheeseburger.

- If we needed to work any more hours this month, we would need food delivery and toilets in every cubicle to make more time for work.

Past contrary to fact conditions

The past versions of the counterfactual conditional sentence require a past perfect (or “pluperfect”) verb in the conditional clause; there is no difference between this form in the indicative and the subjunctive. The main verb still requires a conditional word. The conditional part of the sentence is in the past tense, but the consequence can be in the present tense:

- If I had driven just a little faster yesterday, I might have been caught in that terrible traffic jam that was shown on the news.

- If we had purchased five shares of Microsoft for $105 at its IPO in 1986, those shares would now be worth over $37,000.

Statements of Necessity

Some adjectives and verb phrases that suggest or state that something is mandatory can trigger the appearance of a subjunctive as well; as with other subjunctives, it’s something that hasn’t happened yet, but as with commands and suggestions, somebody thinks that it should happen!

- It is imperative (that)

- It is best (that)

- It is crucial (that)

- It is important (that)

- It is urgent (that)

- It is essential (that)

- It is vital (that)

- It is desirable (that)

- It is a good idea (that)

- It is a bad idea (that)

- It is recommended (that)

As before, some of them have a common alternate construction that does not use the subjunctive:

- It is best to [action]

- It is important to [action]

- It is a good idea to [action]

- It is a bad idea to [action]

- It is essential to [action]

Others on the first list can be put in this alternate construction, but it is less common to do so.

Fearing, with “lest”

The word “lest” introduces what might be called “negative purpose clauses” — doing something in order to prevent something else from happening. The clauses with lest are things that have not happened yet, and the idea is that they should not happen! You can replace the word lest with the phrase “for fear that” to make the sense clear — the first part of the sentence is the action taken or suggested, the second part the (negative) reason for that action:

I went to bed early lest I fall asleep during my morning staff meeting.

She put a lid on the dish lest the food make a mess inside the microwave oven.

Take your time putting that table together lest it collapse in the middle of your dinner party.

The emphasis is on negative things that are undesirable, though this emphasis is stretched a bit at times:

Do not eat at that new Italian restaurant, lest you find yourself wanting to have their delicious lasagna for dinner every night.

Idiomatic Phrases

These are phrases that have remained in English — sometimes in common use! — long after the subjunctive began its retreat into the history of the English language. Some of these are similar to the uses of the subjunctive we’ve had before: some are wishes, some are orders, some are conditions contrary to fact. You may not have seen anything unusual about these before . . . but now you should see the subjunctives in all of them! I’ve put the phrases I believe are more common toward the top, though I don’t have data on the actual usage:

- if need be

- as it were

- if I were you; were I you

- be that as it may

- (God) bless you!

- may the best man win

- come Monday (Tuesday, etc.)

- come what may

- far be it from me (to do [action])

- so be it

- until death do us part

- God save the Queen, God bless America, God rest ye merry gentlemen, etc.

- …need only… (“I need only finish this article to be done with the series”)

- rest in peace

- suffice it to say

- albeit (which is a contraction all be it, another way of saying although it be)

- truth be told

- Heaven forbid (with the thing forbidden also in the subjunctive: Heaven forbid (that) he forget his speech)

- let (may) it be known

- woe betide

- peace be with you

- rue the day

- would that it were (with a sense of I wish it were)